The Creation Team: AtomusPrime - The Project Manager/Developer/misc of all skills. Current Features: Complete re-vamp of the conjuration tree.

(For example you may have 8 skeletons and only be allowed to have 3 draugr) 8 Different types of summons with 5 upgrades for each summon making a total of 48 unique Summons A total of 10 different summoning spells. Conditional limits of how many of each type of summon you may have under your control at once.

Examples of Bad Objectives

If good objectives follow the acronym SMART (specific, measurable, action-driven, realistic, time-bound) then bad objectives conversely do not follow this example. Read these poorly written objectives to get an idea:

- Increase the number of clients our company serves.

- Make customers happy.

- Create some sort of new product.

- Make more money.

- Achieve success.

- Share knowledge.

- Find funding.

- Eliminate quality problems.

The reasons these objectives are bad are because they lack specifics, they don’t rely upon actions, or they focus upon a means to an end rather than an end.

Let’s look at the final example: “Eliminate quality problems.' The statement isn’t specific enough. By changing this objective to be more specific, measurable, action-driven, realistic, and time-bound, it can become a good objective. First, the statement needs to be more specific. What kind of quality problems need to be eliminated? If the product is software, perhaps there need to be fewer bugs in the software. The objective might, then be: Reduce the number of bugs in the software.

This isn’t enough however, because we still don’t know how much reduction is enough. In order to answer this question, the objective can be rewritten to read, “Reduce the number of bugs in the software by 75 percent.' What are the actions that will be taken to reduce the number of bugs? Is this a realistic figure? When will this be completed?

All of these questions must be answered in order to produce an objective that is useful in the project planning process. A final statement of the above objective might be: “Reduce the number of bugs in the software by 75 percent, using careful beta testing and implementing corrections by June.'

Further Reading:

For more information on how to set objectives in project planning, view the following articles:

Ronda Bowen's Project Management Helps Meet Strategic Objectives

Ronda Bowen's Defining the Project Schedule Hierarchy

Donna Cosmato's Real Life Project Management Process Examples

References

Related Articles

- 1 Five Reasons Organizations Develop IT Systems

- 2 Information Technology for Business Success

- 3 Strategy Changes - Company Examples

- 4 Three Examples of Growth at the Corporate Level

Starting in the early 1980s with the first desktop computers, information technology has played an important part in the U.S. and global economies. Companies rely on IT for fast communications, data processing and market intelligence. IT plays an integral role in every industry, helping companies improve business processes, achieve cost efficiencies, drive revenue growth and maintain a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Information Technology in Product Development

Information technology can speed up the time it takes new products to reach the market. Companies can write product requirement documents by gathering market intelligence from proprietary databases, customers and sales representatives. Computer-assisted design and manufacturing software speed up decision making, while collaborative technologies allow global teams to work on different components of a product simultaneously. From innovations in microprocessors to efficient drug delivery systems, information technology helps businesses respond quickly to changing customer requirements.

Information Technology in Stakeholder Integration

Stakeholder integration is another important objective of information technology. Using global 24/7 interconnectivity, a customer service call originating in Des Moines, Iowa, ends up in a call center in Manila, Philippines, where a service agent could look up the relevant information on severs based in corporate headquarters in Dallas, Texas, or in Frankfurt, Germany. Public companies use their investor relations websites to communicate with shareholders, research analysts and other market participants.

Information Technology in Process Improvement

Process improvement is another key IT business objective. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems allow managers to review sales, costs and other operating metrics on one integrated software platform, usually in real time. An ERP system may replace dozens of legacy systems for finance, human resources and other functional areas, thus making internal processes more efficient and cost-effective.

Information Technology and Cost Efficiencies

Although the initial IT implementation costs can be substantial, the resulting long-term cost savings are usually worth the investment. IT allows companies to reduce transaction and implementation costs. For example, the cost of a desktop computer today is a fraction of what it was in the early 1980s, and yet the computers are considerably more powerful. IT-based productivity solutions, from word processing to email, have allowed companies to save on the costs of duplication and postage, while maintaining and improving product quality and customer service.

Cost Savings and Competitive Advantage

Cost savings, rapid product development and process improvements help companies gain and maintain a competitive advantage in the marketplace. If a smartphone competitor announces a new device with innovative touch-screen features, the competitors must quickly follow suit with similar products or risk losing market share. Companies can use rapid prototyping, software simulations and other IT-based systems to bring a product to market cost effectively and quickly.

Information Technology in Globalization

Companies that survive in a competitive environment usually have the operational and financial flexibility to grow locally and then internationally. IT is at the core of operating models essential for globalization, such as telecommuting and outsourcing. A company can outsource most of its noncore functions, such as human resources and finances, to offshore companies and use network technologies to stay in contact with its overseas employees, customers and suppliers.

References (3)

About the Author

Based in Ottawa, Canada, Chirantan Basu has been writing since 1995. His work has appeared in various publications and he has performed financial editing at a Wall Street firm. Basu holds a Bachelor of Engineering from Memorial University of Newfoundland, a Master of Business Administration from the University of Ottawa and holds the Canadian Investment Manager designation from the Canadian Securities Institute.

Cite this Article Choose Citation Style

Basu, Chirantan. 'The Six Important Business Objectives of Information Technology.' Small Business - Chron.com, http://smallbusiness.chron.com/six-important-business-objectives-information-technology-25220.html. 31 January 2019.

Basu, Chirantan. (2019, January 31). The Six Important Business Objectives of Information Technology. Small Business - Chron.com. Retrieved from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/six-important-business-objectives-information-technology-25220.html

Basu, Chirantan. 'The Six Important Business Objectives of Information Technology' last modified January 31, 2019. http://smallbusiness.chron.com/six-important-business-objectives-information-technology-25220.html

Note: Depending on which text editor you're pasting into, you might have to add the italics to the site name.

UN Secretary General Kofi Annan addressing the 6th session of the UN ICT Task Force in New York City, March 25, 2004

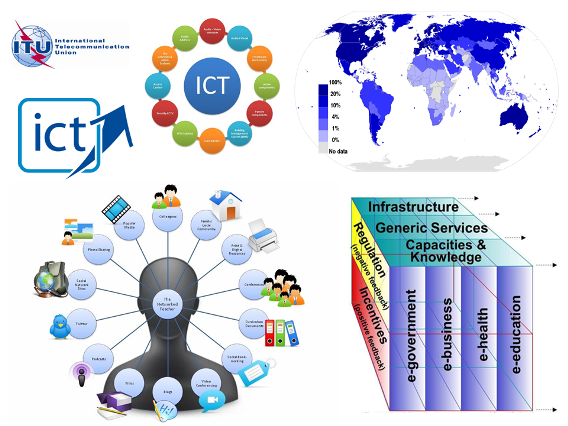

The United Nations Information and Communication Technologies Task Force (UN ICT TF) was a multi-stakeholder initiative associated with the United Nations which is 'intended to lend a truly global dimension to the multitude of efforts to bridge the global digital divide, foster digital opportunity and thus firmly put ICT at the service of development for all'.

- 4Activities

- 5WSIS II in Tunis

- 6Outcomes from WSIS

Establishment[edit]

The UN ICT Task Force was created by United NationsSecretary-GeneralKofi Annan in November 2001, acting upon a request by the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) dated July 11, 2000, with an initial term of mandate of three years (until the end of 2004). It followed in the footsteps of the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Digital Divide Initiative (GDDI), and the Digital Opportunities Task Force (DOT Force), established in 2000 by the G8 at their annual summit in Okinawa, Japan. By providing it with a home in the United Nations, this accorded the UN ICT Task Force, in the eyes of many developing countries, a broader legitimization than the previous WEF and G8 initiatives, even if these previous initiatives also included a multi-stakehoder approach with broad participation by stakeholders from industrialized and developing countries.

Aims and objectives[edit]

The Task Force's principal aim was to provide policy advice to governments and international organizations for bridging the digital divide. In addition to supporting the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) and leading the UN in developing ICT strategies for development, the Task Force's objective was to form partnerships between the UN system and states, private industry, trusts, foundations and donors, and other stakeholders.

Membership and organization[edit]

The UN ICT Task Force has included the top ranks of the computer industry (Cisco Systems, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Nokia, SAP, Siemens, Sun Microsystems), together with global NGOs (e.g., the Association for Progressive Communications), governments and international agencies. Its coordinating body was a multi-stakeholder bureau, assisted by a small secretariat at UN headquarters in New York. Technical advice was provided by a high-level panel of technical advisors.

Activities[edit]

United Nations Information Technology Service (UNITeS)[edit]

Within the Report of the high-level panel of experts on information and communication technology (22 May 2000) suggesting a UN ICT Task Force, the panel welcomed the establishment of a United Nations Information Technology Service (UNITeS), suggested by Kofi Annan in 'We the peoples: the role of the United Nations in the 21st century' (Millennium Report of the Secretary-General). The panel made suggestions on its configuration and implementation strategy, including that ICT4Dvolunteering opportunities make mobilizing 'national human resources' (local ICT experts) within developing countries a priority, for both men and women. The initiative was launched at the United Nations Volunteers under the leadership of Sharon Capeling-Alakija and was active from February 2001 to February 2005. Initiative staff and volunteers participated in the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in Geneva in December 2003.[1]

Challenge to Silicon Valley[edit]

In November 2002 Kofi Annan issued a Challenge to Silicon Valley to create suitable systems at prices low enough to permit deployment everywhere.[citation needed] The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees ran a refugee camp in Tanzania where the Global Catalyst Foundation had placed computers and communications equipment for the use of the Burundian refugees confined there. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) worked with the Kingdom of Bhutan on a Simputer project.

World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS)[edit]

The Task Force was active, inter alia, in the process leading to the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in Geneva in December 2003 and WSIS II in Tunis, Tunisia, in November 2005. In order to participate in the second phase of the WSIS, the Task Force's original three-year mandate was extended by another year and expired on 31 December 2005, with no further extension.

Working groups[edit]

The Task Force's stakeholders, members and the experts on the panel of technical advisors, were active in working groups organized around four broad themes:

- ICT policy and governance

- Enabling environment

- Human resource development and capacity building

- ICT Indicators and MDG mapping

Regional networks[edit]

Regional activities were carried out in five regional networks—Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, Arab States, and Europe and Central Asia.

Meetings[edit]

2002, June 17–18: A session of the General Assembly of the United Nations was devoted to information and communication technologies for development, addressing the digital divide in the context of globalization and the development process. The session promoted coherence and synergies between various regional and international information and communication technologies initiatives. The meeting also contributed to the preparation of WSIS. Many countries were represented by high-level officials responsible for communications and for development.

The Task Force held 10 semi-annual meetings in various places that served as important venues for exchange of best practices, and to bring the various stakeholders together to work on common themes. Most successful, in the eyes of the participants, were those meetings that were held in conjunction with a series of Global Forums:

- 1st meeting: at UN headquarters in New York City, NY, (United States) - November 19–20, 2001.

- 2nd meeting: at UN headquarters in New York City, NY, (United States) - February 3–4, 2002.

- 3rd meeting: at UN headquarters in New York City, NY, (United States) - September 30 - October 1, 2002, focused on ICT for development in Africa. It also reviewed the results of the first year of Task Force activities and agreed on an ambitious strategy for the next two years.

- 4th meeting: at UN in Geneva, (Switzerland) - February 21–22, 2004, with a Private Sector Forum.

- 5th meeting: at WIPO in Geneva - September 12–13, 2003, to allow participants to discuss the Task Force's contribution to WSIS.

- 6th meeting: at UN headquarters in New York City, NY, (United States) - March 2004, with a Global Forum on Internet Governance.

- 7th meeting: at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin, Germany - November 18–20, 2004, with a Global Forum on an Enabling Environment.

- 8th meeting: in Dublin, Ireland - April 13–15, 2005, with a Global Forum on Harnessing the Potential of ICTs in Education.

- 9th meeting: at ILO in Geneva, Switzerland - October 1, 2005.

- 10th (final) meeting: at the World Summit on the Information Society in Tunis, Tunisia - November 17, 2005.

In addition, a Global Roundtable Forum on 'Innovation and Investment: Scaling Science and Technology to Meet the MDGs' was held in New York City, 13 September 2005. The primary focus of the Forum was on the critical role of science, technology and innovation, especially information and communication technologies, in scaling-up grassroots, national and global responses to achieve the Millennium Development Goals.

WSIS II in Tunis[edit]

Parallel to the booth at the ICT4ALL exhibition, a series of events was held under the auspices of the UN ICT Task Force and its members:

Measuring the Information Society[edit]

The Partnership for Measuring ICT for Development[2] involves 11 organizations—Eurostat, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations ICT Task Force, the five United Nations Regional Commissions and the World Bank.

Role of Parliaments in the Information Society[edit]

Key parliament leaders presented their views on the role that national and regional assemblies can play in building the information society at a “High-level Dialogue on Governance, Global Citizenship and Technology”, on 16 November. Install

ablebits.

Choosing the Right Technologies for Education[edit]

At this workshop, the Global e-School Initiative[3] presented the Total Cost of Ownership Calculator—a framework for identifying and selecting the right ICT for schools by assessing their benefits, feasibility and costs.

Building Partnerships for the Information Society[edit]

Two high-level round tables on 16 November focused on “Regional Perspectives for the Global Information Society” and on “Women in the Information Society: Building a Gender Balanced Knowledge-based Economy”.

Putting ICT to Work for the Millennium Development Goals and the UN Development Agenda[edit]

Aim And Objectives Of Ict

The 17 November round table examined how ICT can be applied to the achievement of the internationally agreed development goals, and discussed ways to raise awareness of ICT as an enabler of development.

Achieving Better Quality and Cost Efficiency in Health Care and Education through ICT[edit]

The 17 November panel demonstrated the potential of ICT to improve quality and cost efficiency of key public services, with specific focus on education and health care.

Aims And Objectives Of Education

Bridging the Digital Divide with Broadband Wireless Internet[edit]

The 17 November round table focused on the critical role that broadband wireless infrastructure deployments play in bridging the digital divide.

Outcomes from WSIS[edit]

GESCI[edit]

One of the notable outcomes of the work of the UN ICT Task Force was the creation in 2003 of the Global E-Schools and Communities Initiative (GESCI), an international NGO initially located in Dublin, Ireland, to improve education in schools and communities through the use of information and communication technologies.[3] GESCI was officially launched during the WSIS.

Today GESCI (www.gesci.org) is located in Nairobi, Kenya. It has evolved into an organization engaging with governments and ministries, development partners, the private sector and communities to provide strategic advice, coordinate policy dialogue, conduct research and develop and implement models of good practice for the widespread use and integration of ICTs in formal education and other learning environments, within the context of supporting the development of inclusive knowledge societies and the achievement of the SDGs.

ePol-Net[edit]

Another outcome is the Global ePolicy Resource Network (ePol-NET),[4] designed to marshal global efforts in support of national e-strategies for development. The network provides ICT policymakers in developing countries with the depth and quality of information needed to develop effective national e-policies and e-strategies. The network was first proposed by the members of the Digital Opportunities Task Force (DOT Force), who merged their activities with the UN ICT Task Force in 2002. The ePol-Net was also officially launched during the WSIS.

Global Centre for ICT in Parliament[edit]

Another outcome of the WSIS is the Global Centre for ICT in Parliament. Launched by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) in cooperation with the Inter-parliamentary Union (IPU) on the occasion of the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS) in Tunis in November 2005, the Global Centre for Information and Communication Technologies in Parliament responds to the common desire to build a people-centred, inclusive and development-oriented information society, where legislatures are empowered to better fulfill their constitutional functions through Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

The Global Centre for ICT in Parliament acts as a clearing house for information, research, innovation, technology and technical assistance, and promotes a structured dialogue among parliaments, centres of excellence, international organizations, the civil society, the private sector and the donor community, with the purpose to enhance the sharing of experiences, the identification of best practices and the implementation of appropriate solutions.

Follow-up[edit]

The task of bridging the digital divide is yet unfinished. The WSIS has called for an Internet Governance Forum[5] to allow for a global multi-stakeholder discussion of issues related to the governance of the global resource that the Internet represents. The WSIS also called for a follow-up and implementation process, for which the principles embodied in the multi-stakeholder composition and workings of the UN ICT TF can provide a useful model.

Work is also being carried on by the UN Group on the Information Society (UN GIS),[6] with a focus on the UN System, and the successor to the UN ICT TF, the Global Alliance for ICT and Development (GAID),[7] with an international development emphasis.

Definition Of Aims And Objectives

Selected documents[edit]

- Report of the high-level panel of experts on information and communication technology (22 May 2000), suggesting a UN ICT Task Force.

- Draft Ministerial Declaration (11 July 2000), asking for the establishment of the UN ICT TF.

Publication series[edit]

As part of its work, the Task Force and its members have published a series of books on various topics related to the work of the Task Force. These books are available in the UN bookstore, at Amazon (partially), or in PDF form:

- UN ICT Task Force Series 1 - Information Insecurity: A Survival Guide to the Uncharted Territories of Cyber-Threats and Cyber-Security (By Eduardo Gelbstein, Ahmad Kamal) - July 2005, ISBN92-1-104530-4

- UN ICT Task Force Series 2 - Information and Communication Technologies for African Development: An Assessment of Progress and Challenges Ahead (Edited with Introduction by Joseph O. Okpaku, Sr., Ph.D.) - July 2005, ISBN92-1-104531-2

- UN ICT Task Force Series 3: The Role of Information and Communication Technology in Global Development - Analyses and Policy Recommendations (Edited with introduction by Abdul Basit Haqqani) - July 2005, ISBN92-1-104532-0

- UN ICT Task Force Series 4: Connected for Development: Information Kiosks and Sustainability (By Akhtar Badshah, Sarbuland Khan and Maria Garrido) - July 2005, ISBN92-1-104533-9

- UN ICT Task Force Series 5 - Internet Governance: A Grand Collaboration (By Don MacLean) - July 2005, ISBN92-1-104534-7

- UN ICT Task Force Series 6 - Creating an Enabling Environment: Toward the Millennium Development Goals[permanent dead link] (By Denis Gilhooly) - September 2005, ISBN92-1-104535-5

- UN ICT Task Force Series 7 - WTO, E-commerce and Information Technologies: From the Uruguay Round through the Doha Development Agenda (By Sacha Wunsch-Vincent, Edited by Joanna McIntosh)

- UN ICT Task Force Series 8: The World Summit on the Information Society: Moving from the Past into the Future (Edited by Daniel Stauffacher and Wolfgang Kleinwächter)

- UN ICT Task Force Series 9: Harnessing the Potential of ICT for Education – A Multistakeholder Approach (Edited by Bonnie Bracey and Terry Culver)

- UN ICT Task Force Series 10: Village Phone Replication Manual (By David Keogh and Tim Wood) - September 2005, ISBN92-1-104546-0

- UN ICT Task Force Series 11: Information and Communication Technology for Peace - The Role of ICT in Preventing, Responding to and Recovering from Conflict (By Daniel Stauffacher, William Drake, Paul Currion and Julia Steinberger)

- UN ICT Task Force Series 12: Reforming Internet Governance: Perspectives from the Working Group on Internet Governance (WGIG) (Edited by William J. Drake)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^'UNITeS'. Archived from the original on 31 August 2004. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^Welcome to the Measuring ICT Website - new.unctad.orgArchived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ abGlobal eSchools and Communities Initiative

- ^'Global ePolicy Resource Network'. Archived from the original on 2006-01-05. Retrieved 2005-12-29.

- ^Internet Governance Forum

- ^Group on the Information Society

- ^Global Alliance for ICT and DevelopmentArchived February 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

Retrieved from 'https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=United_Nations_Information_and_Communication_Technologies_Task_Force&oldid=886714392'

The Compact Oxford English Dictionary and others interchangeably define the noun 'objective' as, Objective: noun 1 a goal or aim.[1] Although the noun forms of the three words aim, objective and goal are often used synonymously, professionals in organised education define the words aim and objective more narrowly and consider them to be distinct from each other.

Aims are concerned with purpose whereas objectives are concerned with achievement.

Usually an educational objective relates to gaining an ability, a skill, some knowledge, a new attitude etc. rather than having merely completed a given task. Since the achievement of objectives usually takes place during the course and the aims look forward into the student's career and life beyond the course one can expect the aims of a course to be relatively more long term than the objectives of that same course.[2][3]

. Sometimes an aim sets a goal for the teacher to achieve in relation to the learners, sometimes course aims explicitly list long-term goals for the learner and at other times there is a joint goal for the teacher and learner to achieve together. While the aim may be phrased as a goal for the teacher within the scope of the course it can also imply goals for the learner beyond the duration of the course. In a statement of an aim the third personsingular form of the verb with the subjectcourse, programme or module is often used as an impersonal way of referring to the teaching staff and their goals. Similarly the learner is often referred to in the third person singular even when he or she is the intended reader.

Course objectives[edit]

An objective is a (relatively) shorter term goal which successful learners will achieve within the scope of the course itself. Objectives are often worded in course documentation in a way that explains to learners what they should try to achieve as they learn. Some educational organisations design objectives which carefully match the SMART criteria borrowed from the business world.

Learning outcomes[edit]

Since both aim and objective are in common language synonymous with goal they are both suggestive of a form of goal-oriented education. For this reason some educational organisations use the term learning outcome since this term is inclusive of education in which learners strive to achieve goals but extends further to include other forms of education. For example, in learning through play children are not made aware of specific goals but planned, beneficial outcomes result from the activity nevertheless.

Therefore, the term learning outcome is replacing objective in some educational organisations. In some organisations the term learning outcome is used in the part of a course description where aims are normally found.[4][5] One can equate aims to intended learning outcomes and objectives to measured learning outcomes. A third category of learning outcome is the unintended learning outcome which would include beneficial outcomes that were neither planned nor sought but are simply observed.

See also[edit]

- Bloom's taxonomy, a classification of learning objectives

References[edit]

- ^Compact Oxford English Dictionary

- ^University of Nottingham, Medical School, Learning Objectives

- ^Teaching Sociology, Vol. 8, No. 3, Why Formalize the Aims of Instruction?

- ^Developing Outcomes and Objectives, The Learning Management Corporation

- ^Outcomes Versus Objectives? What’s the Difference? Daniel Pittaway

Retrieved from 'https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Educational_aims_and_objectives&oldid=872668610'